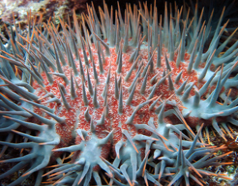

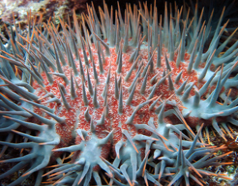

Crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) (Acanthaster planci) naturally occur on coral reefs. They are corallivores (i.e., they eat coral polyps). Covered in long poisonous spines, they range in color from purplish blue to reddish-gray to green. They are generally 25-35 cm in diameter, although they can be as large as 80 cm.

Crown-of-thorns starfish are found throughout the Indo-Pacific region, occurring from the Red Sea and coast of East Africa, across the Pacific and Indian Oceans, to the west coast of Central America. Predators of COTS include the giant triton snail, the stars and stripes pufferfish (Arothron hispidus), the titan triggerfish (Balistoides viridescens), and the humphead maori wrasse (Cheilinus undulates).

Crown-of-thorns starfish prey on nearly all corals, and their feeding preferences and behavior patterns vary with population density, water motion, and species composition. COTS typically prefer to feed on branching and table corals (e.g., Acropora), which are the same genera that are most vulnerable to bleaching. However, when branching coral cover is low due to overabundance of COTS or environmental conditions, COTS may eat other corals such as Porites or foliose corals (e.g. Montipora). In addition to hard corals, COTS may also eat sponges, soft corals, algae, and encrusting organisms.

COTS Outbreaks

Although COTS occur naturally in low numbers on coral reefs, they sometimes appear in high densities called “outbreaks”. The natural density of COTS is 6-20 km2 which is less than 1 per hectare. An outbreak is usually defined as 30 or more adult starfish per hectare on reefs, or when they reach densities such that the starfish are consuming coral tissue faster than the corals can grow. COTS can consume live coral at a rate of 5-13 m2 per year.

Through occasional outbreaks, COTS can play a valuable role in reef ecosystems by helping to maintain coral species diversity. In some cases, the frequency of outbreaks and associated coral mortality is about the same as coral growth and recovery rates. COTS may help create space for slow-growing massive corals because COTS prefer to eat the faster-growing corals. However, anthropogenic and other stresses combined with more frequent COTS outbreaks can result in significant damage to reefs, and COTS are now considered a main source of coral mortality on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Healthy reefs can recover from COTS outbreaks within 10 to 20 years, but degraded reefs facing a variety of stressors and climate change are less resilient and may not recover between outbreaks.

COTS outbreaks appear to be increasing in frequency over the last several decades, and they have caused widespread damage to coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific. Dense aggregations of COTS can strip a reef of 90% of living coral tissue. In the 1970s on the northern Great Barrier Reef, a COTS outbreak occurred that lasted eight years. This outbreak peaked with about 1000 starfish per hectare, leaving 150 reefs devoid of coral, and 500 reefs damaged. In the Togian Islands in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, over 80% of coral on a reef was destroyed by a COTS outbreak. Damage from COTS can indirectly affect fish populations that depend on coral reefs for habitat. On the Great Barrier Reef, two species of butterfly fish that eat coral and two species of plankton feeding fish dramatically declined following outbreaks of COTS.

What Causes COTS Outbreaks?

Scientists are not sure what causes outbreaks of COTS, but one of the most widely accepted hypothesis is that COTS outbreaks are predominantly controlled by phytoplankton availability.Nutrient enrichment from agricultural land runoff may lead to COTS outbreaks because elevated nutrient levels cause phytoplankton blooms which provide a necessary food source for COTS larvae. For example, in the Great Barrier Reef, doubled concentrations of large phytoplankton were linked to nearly a 10-fold increase in larval development, growth and survival of COTS. Other scientists believe that COTS outbreaks are linked to the timing of

El Niño events or are driven by removal of COTS predators.

Control of COTS

Programs have been developed to

control COTS. Methods for COTS control include taking starfish ashore and burying them, injecting them with compressed air, baking them in the sun, injecting them with toxic chemicals (e.g., formalin, ammonia, copper sulphate), and building underwater fences to control COTS movement. The recommended method on the Great Barrier Reef is to inject bile salts into the starfish which kills the starfish but does not harm the surrounding reef ecosystem. Mechanical methods for controlling COTS are expensive and labor intensive, thus may only be justified in small reefs that have high socioeconomic or biological significance, such as important spawning sites, tourist attractions, or areas with extremely high biodiversity.